Maggie Vail

In the 19th century, divorce was rare if not impossible for most Canadians and women were judged by a strict moral code; men, on the other hand, were given some leeway to 'sew their wild oats.'

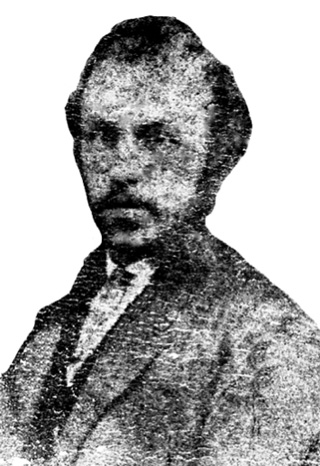

In 1869 Saint John was rocked by a scandal that included adultery, an illegitimate child and a double murder. The alleged killer was a middle-aged professional, a respectable married architect with a wife and children. The trial scandalized and fascinated the people of Saint John, who heard and read about legal testimony dealing with seduction, adultery, male responsibility and brutal violence that reached into the city’s respectable classes.

Discovery of the crime: The Inquest

In the fall of 1869, a number of African Canadian residents of Simonds parish, east of Saint John, made a grisly discovery when picking berries in the Loch Lomond area. Amongst some bushes on the "blueberry plains" near Black River Road they came across what appeared to be human remains.

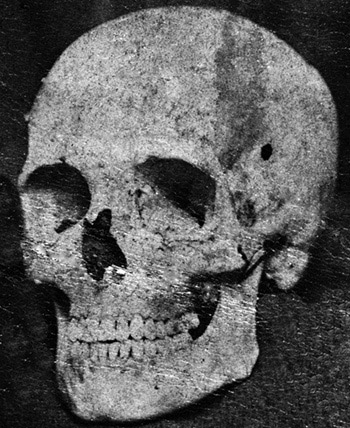

Further examination revealed the partial skeletal remains of a woman and child, and the county coroner, Dr. Sylvester Earle, was notified. The skull of the child revealed marks of foul play. The coroner convened an inquest, which involved several witnesses giving evidence before a jury of six men. Key to the later trial was testimony that suggested that in 1868 a mysterious young woman had attempted to pass herself off as a Mrs. Kane, and her child as the child of Mr. Kane.

Following the arrest of James Kane, the coroner ordered the apprehension of John A. Munroe, a Saint John architect. Testimony from a coachman established that Munroe had arranged for the conveyance of a "Mrs. Clark" and young child to the Black River Road in 1868.

Around the same time, Munroe arranged to send Clark's trunk on the steamer to Boston. When the coachman returned to pick up Munroe in the countryside, he was alone. The woman and child, he had been informed, were staying with friends. A woman who kept a hotel in the city where Mrs. Clark stayed temporarily before disappearing testified that she had suspected that Munroe, a married man, was the father of her child, Ella May.

The inquest also heard from Jacob Vail, a house carpenter who lived in Carleton, a Saint John suburb. He testified that in 1867 he had heard rumours that his niece, Sarah Margaret Vail, was keeping company with Munroe, a married man. Vail's sister confirmed that she gave birth to a child out of wedlock on Feb. 4, 1868 and that the father was John Munroe.

Munroe, furthermore, had spoken of poisoning his wife after the birth of his child. One issue that arose during the trial as a possible motive is that Maggie Vail possessed several hundred dollars in cash, after selling a house and land that she had inherited from her father.

Munroe did not testify before the inquest, but his statements to police were recorded. The architect claimed that he knew Miss Vail from Carleton, and that she had been on the same steamer which he had taken to Boston. He told police that at Boston Vail planned to meet a man who had promised to marry her. Vail had returned to New Brunswick and had persuaded Munroe to escort her and her child to Loch Lomond where she was supposedly visiting friends.

Victorian forensics

The two bodies had been covered by branches and moss, which indicated foul play.

The two bodies had been covered by branches and moss, which indicated foul play.

Other than circumstantial evidence, there was little to pinpoint Munroe as the killer, even if he did have a motive – to avoid scandal or blackmail, or having to support a mistress and her child – and opportunity. No murder weapon or bullet was ever found. Vail's remains were identified by detailed testimony concerning her teeth, hairstyle and clothing.

Dr. Earle enlisted the expertise of two colleagues, Dr. James Christie and Dr. LeBaron Botsford, to examine the forensic evidence, notably the skull whose condition suggested that the victim had been shot in the head.

One doctor visited the crime scene where he collected "brain matter," bones and bone fragments, and a tooth of a 12-14 month old child.

Christie performed experiments on another skull, which he covered with muscular tissue and filled with water. He then shot three bullets into the skull and a range of two feet and concluded that the victim had died in this manner.

The coroner had also engaged a land surveyor to prepare a detailed plan of the crime scene, which was near the junction of the Black River Road and Quaco Road. The prosecution brought in three dentists who attempted to establish the age of the two victims based on their teeth.

The defence counsel produced a prominent Saint John doctor who testified that it was impossible to identify the adult skeletal remains, which had been damaged by animals, as either male or female.

Both the Crown and the defence conducted various tests with firearms at the crime scene. The defence contended that pistol shots fired at the site would have been easily heard by nearby settlers. Other technical evidence submitted to the court the prosecution included meteorological records to prove the condition of the ground in October, 1868 and tidal charts to establish the position of a steamship in Saint John harbour.

The trial

After the coroner’s jury registered verdicts of willful murder against John A. Munroe, for the murder of Sarah Margaret Vail and Ella May Munroe, the coroner issued a warrant to commit Munroe to the county jail. Given his social position, professional connections and standing in the community, people were shocked that he was placed in handcuffs.

He admitted to knowing Vail, and having attempted to assist her, but denied that he was the father of her child.

The next stage was the examination before police magistrate Humphrey T. Gilbert, where the testimony before the coroner’s inquest was essentially repeated, with additional evidence from the coroner.

Dr. Earle revealed that the accused had voluntarily informed him, during the course of the inquest, that he had agreed to take mother and child out to the Black River Road near Loch Lomond to meet a person Vail expected to marry. He had let them proceed on foot so that he would not be seen by the unnamed party, and returned to the waiting coachman at a nearby inn. It appeared that Munroe was the last person to be seen with Maggie Vail prior to her disappearance.

The St. John Circuit Court, under Judge Allan, began hearing the case on December 7, 1869. The trial drew large crowds of spectators. The prosecution was handled by the Attorney General of New Brunswick, A.R. Wetmore, assisted by W.H. Tuck. Munroe was defended by prominent barrister S.R. Thomson.

One issue discussed early in the proceedings was whether newspaper coverage had prejudiced the case for the defence. The defence was permitted to challenge a dozen potential jurors, but the defendant had no right to testify. On the other hand, unlike in capital trials earlier in the century, the defence lawyer was at least permitted to address the jury.

Press accounts of the trial noted the testimony of the "coloured" witnesses of the Willow Grove area, a community formed by American refugees from the War of 1812. A store clerk testified that the defendant had purchased a Smith and Wesson seven-barrel .22 calibre revolver in the fall of 1868.

The Crown also produced most of the residents of the area to which Vail, according to Munroe's statement, had been heading, either to visit friends or to meet a man she intended to wed. None of the residents of that section of Black River Road had known a Maggie Vail or a Mrs. Clark (Vail's assumed name at the time).

Testimony by a coachman and others placed Munroe, Vail and her daughter at Willow Grove on the afternoon of Halloween, 1868. The trunk sent to Boston in the fall of 1868 was never claimed; it was returned to New Brunswick a year later at the request of the authorities and its contents became evidence in the trial.

The defence counsel attempted to have Munroe's statement to the police chief of Portland, a suburb of Saint John, excluded. The police officer testified that Munroe had been warned by the police magistrate not to make any statement without first talking to a lawyer, but that the prisoner had conversed freely, despite also being cautioned by the police chief of Saint John.

Thomson criticized the role of police chief, a personal acquaintance of the accused, who had promised to keep his conversation confidential. The defence enlisted a host of character witnesses, including the sheriff and deputy sheriff of the county, and asked the jury to consider why his client, a married man with a prosperous professional practice, would risk everything by committing such a crime, especially when his relationship with Miss Vail was so widely known.

Thomson attempted to prove that the trunk purporting to be Vail's had been made in the United States, not new Brunswick, and that there was no proof that the bodies discovered at Willow Grove were Vail and her child. A last-minute defence witness, a farmer from Sussex, claimed to have given a lift in his wagon to a young woman and child from Willow Grove to Saint John, where they boarded the steamer to Boston.

Given the compelling weight of circumstantial evidence against Munroe, the defence appealed to the jury's emotions, and attacked the police, the coroner, the police magistrate, and the criminal law itself for undermining British justice.

Verdict

In his charge to the jury, Judge Allan explained that many cases in English and Canadian law had turned on circumstantial evidence. The judge summed up the evidence on three key questions: Were the remains those of Vail? Had she been murdered? Had she been murdered by the accused? The jury came back with a guilty verdict, which in 1869 was an automatic death sentence, but with a strong recommendation of mercy. Supporters of Munroe circulated a petition urging the government to exercise clemency.

Sentence: December 21, 1869

On the day the judge was scheduled to pronounce sentence, disorder prevailed, as 1500 persons, including noisy boys, crowded into the court room, the hall and the stairway, and the street outside. Judge Allan noted that the jury's recommendation for mercy was probably motivated by concern for the prisoner's family; he would forward the request to Ottawa but entertained no hope of a favourable outcome:

You should use all the time you have to spare in this world in seeking forgiveness from Almighty God for your many sins, as you cannot hope for mercy from man. I shall not refer to anything that might wound your feelings, but all I shall say is that the unfortunate woman who placed reliance in you was hurried before her Maker without that preparation which, so far as we can judge, she sorely needed. You shall have further time to prepare for death and for obtaining that forgiveness you so much need.

Munroe's confession

Munroe's confession on the eve of his death. The confession, dated February 14, 1870, was witnessed by Reverend Charles Stewart and Reverend James Lathern. Interestingly, the prisoner expressed no remorse and asked for no forgiveness:

The first time I went out with Miss Vail it was only for a ride; we had no quarrel, and our going out was at her wish. When we got out of the coach, at or near the place described on the trial, she had a satchel, and we walked along the road, I cannot say how far. Sat down and had a little target practice; both fired at a mark, she using a pistol I gave to her one of a pair- a breach loader same as my own, the mate of it I gave to a friend.

I had learned her how to use it. There was no intention on my part to harm her at that time. We came back, and I left her at Lake's; she was to have gone to Boston on the Thursday after the first going out but it was too stormy, and I went with my wife to Fredericton on that day, and came down again on Friday night. It was during that trip to Fredericton I first thought that the spot I had visited with Miss Vail was a suitable spot to commit a bad act.

I went out again with Miss Vail on the Saturday following; we went the same road as before and to about the same place. The morning was frosty, the moss was crisp and hard; there was no one on the barren; the road was a little muddy. We went off the road a little way together and sat down; I went into the bushes; the child cried; I came out again-was angry. I strangled the child. I do not know if it was actually dead.

As she was rising up I shot her (Miss Vail) in the head .. …I cannot say that money was not one of the motives for the act committed. I do not say it was in self defence I killed Miss Vail. It was the money, my anger with her at the time and my bad thoughts on and after the trip to Fredericton, working together, caused me to do the bad act. The letter written to Mrs. Crear was written by me and mailed by a friend of mine living in or near Boston. I never killed any other person or child.

Execution: February 15, 1870

The prisoner, according to an account published by George Day, was visited by clergymen the evening before his execution, and was calm and resigned to his fate.

He went to sleep at midnight and rose at 4:00 am, dressed and prayed. As the dawn broke and the morning came he was joined by the clergymen, magistrates, the Coroner’s jury and other officials, as well as local newspaper reporters. At 7:45 am a bell began to toll, and the black flag of death was raised over the gaol. The prisoner, appearing "pale and anxious," was escorted to the gallows platform by the sheriff and the two ministers.

Prior to Munroe leaving the death cell, the noose had been placed around his neck, while a clergyman advised him "not to think of earthly things, but to fix his mind on the Saviour of Mankind."

Unlike earlier hangings, this one took place out of public sight, in the gaol yard. The gallows device was a new mechanism, consisting of a beam, one end of which was attached to the noose. The other end was attached to a heavy weight, suspended by a rope. When the rope was cut, the beam rose in the air, lifting the condemned man.

One account recorded: "when the fatal cord was cut, and the miserable man jerked form terra firma, and was suspended in the air two feet from the platform. He struggled hard, and his sufferings appeared to be terrible."

Unlike the case of Breen who was hanged in 1857 and buried on the grounds of the Alms House, and other executed prisoners elsewhere in Canada who were buried within the walls of the local jail, in this case Munroe's corpse was released to his family for Christian burial.

One footnote in this case concerns Munroe's wife, Annie Potts, whom he had married in 1862. In 1878 she remarried Edwin Snider.

The last execution in Saint John took place in November of 1956. Clifford Ayles, 26 years old, was hanged for the murder of a robbery victim in 1955. The last person to be hanged in the province was J.P. Richard, who was executed at Dalhousie in 1957 for sexually assaulting and strangling a 13-year-old girl.

Bibliography

The Black River Road Tragedy: Full reports of the coroner's inquest and the trial of John A. Munro for the murder of Sarah Margaret Vail and Ella May Munroe (Saint John: G.W. Day, 1870)

Also available on microfiche as CIHM no. 11172. Saint John Morning News, Sept.-1869-March 1870.