Course syllabus

A syllabus is the course planning document. It may be short but a lot of thought and effort goes into making it. This article discusses what goes into creating a course syllabus. On the UNB SharePoint site (UNB login required), we share a Customizable Syllabus Template (Word Doc) that can be modified for use in UNB courses.

To create the syllabus, you think about:

- What students should know and be able to do after completing the course

- The topics to be covered and the content to support them

- To what level of learning students should master each topic

- What teaching techniques you will use to enable students to reach the learning level required

- How students will demonstrate what they know and can do (assignments, tests, projects, etc.)

- How you can be sure that assessment activities measure what is important in the course (that is, they are weighted to match the relative importance of the course topics and skills)

In the syllabus, you document your decisions about each of the items above, typically by including the following:

- Course pre-requisites and co-requisites

- Course outcomes statements

- A list of course topics and a schedule of when they will be taught

- A list of assessment items, with brief descriptions of each and due dates

- Marking scheme with assessment items and weighting

- Citations for textbook and/or other materials in which students will find the majority of the topic / lab content, reserve materials, and any other recommended optional resource materials

- Your class and course policies (e.g., on attendance, late assignment submissions, classroom decorum, use of educational technology)

- Your contact information and availability, and that of others involved in course delivery as appropriate, such as Teaching Assistants.

- University statement on plagiarism

- Details about labs location and schedule, location of online course components, etc.

See university calendar for more details.

1. What students should know and be able to do after taking the course

Check department and program course and curriculum regulations and outcomes, if they exist, and determine how your course fits within them.

Think about your student audience. What is their age range, program, year, and experience, both life experience and experience in the discipline? What are their likely interests, needs, goals, expectations? How much diversity (language, culture, learning styles) will there be in the class? What teaching methods are they most responsive to? What skills do they have and should they have before they leave the course?

Make a list of the knowledge and skills students should have when they leave your course (what they should know and can do). Examples include:

- Knowing facts, concepts, principles, processes, and procedures

- Understanding and applying knowledge, critical analysis and thinking

- Problem solving

- Discovering relationships among different components of knowledge

- Developing new knowledge

- Learning skills for performing tasks in the discipline

- Developing attitudes or values appropriate to the discipline (scientific inquiry methods, finding evidence to support ideas and assertions, etc.)

- Creating and refining mental models of the topic area

- Developing evidence-based worldviews

- Learning how to learn and how to reason by thinking about, talking about, and discussing the process of learning and reasoning (metacognition)

Condense these into four or five statements that complete the sentence, “Upon completion of the course, you should be able to:"

Examples:

- Make comparisons between a range of health contexts, such as individual and institutional and national and international contexts;

- Analyse health and health issues, and health information and data that may be drawn from a wide range of disciplines;

- Synthesize coherent arguments from a range of contesting theories relating to health and health issues;

- Draw upon the personal and lived experience of health and illness through the skill of reflection and to make links between individual experience of health and health issues and the wider structural elements relevant to health;

- Articulate central theoretical arguments within a variety of health studies contexts;

- Draw on research and research methodologies to locate, review and evaluate research findings relevant to health and health issues, across a range of disciplines.

Outcomes checklist. Do your outcomes statements:

- Align with program outcomes and prerequisite and subsequent courses?

- Focus on what the student will know and do, rather than content or what is taught?

- Describe learning, rather than a learning activity?

- Use verbs that describe actions that can be observed and measured?

- Make it possible to determine the learning level (e.g., comprehension, analysis, application, etc.) from the information provided? This is important for learning activity and assessment design.

2. Topics to be covered and the content to support them

Item 1 provides the framework in which to do item 2. List the content topics that will enable students to achieve the course learning objectives or outcomes.

Course content should:

- Fit with your list of course outcomes

- Have importance in the discipline

- Be based on or related to research

- Appeal to student interests

- Build upon student past experience or knowledge without duplicating it

- Be multi-functional (help teach more than one concept, skill, or problem)

- Encourage further investigation

- Show interrelationships amongst concepts

- Be sufficiently significant to help students build and refine their mental models of the subject area

To determine your topic listing and structure, you could try drawing concept maps of the subject area; write topics on index cards and shuffle to create the order you want. Typical organizational schemes include most to least importance, logical sequence, simplest to most complex, items prerequisite to others, problem-centred, and spiral (teaching related content topics sequentially to a certain level of detail, then going back and teaching them again in more detail).

3. To what level of learning students should master each topic

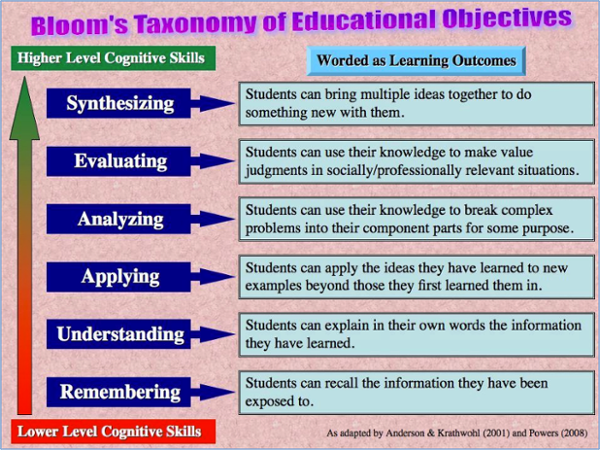

Table 1 shows what level of learning is involved in each outcome statement as determined from the outcome wording. This is significant because different teaching methods are effective for different levels of learning, in order for students to master knowledge and skills to that level.

For each of your course learning objectives or outcomes, determine which learning level is the one to which students will be expected to master the content, then select teaching methods appropriate to that level, as described in section 4.

4. What teaching techniques you will use to enable students to reach the learning level required

The table below lists possible teaching methods for each of Bloom’s learning levels in the cognitive domain, with the lowest learning levels at the bottom.

| Level | Teaching Methods |

|---|---|

| Synthesizing | Assignments or projects in which students create something new that may include ideas or content from acknowledged sources, but is original. |

| Evaluating | Assignments, projects, or problems in which students find and use existing criteria to evaluate a wide variety of situations, problems, conceptual expressions, projects, developed items… |

| Analyzing | Scenarios, case studies, moving from well-structured to “ill-structured2” problems of increasing complexity (low fidelity to high fidelity), breaking down problems into component parts, class presentations, “trade show” or “conference poster” projects |

| Applying | “Well-structured1” (low fidelity—simplified for instructional purposes) scenarios and case studies, class presentations, “trade show” or “conference poster” projects |

| Understanding | Discussion, writing, presenting (students explain in own words), peer instruction, analogies, metaphors, creating concept maps and flowcharts |

| Remembering | Drill and practice activities, such as practice tests, quizzes, jeopardy-style question-and-answer games, examples and non-examples (well-structured) diagrams or similar informational displays with descriptive labels and/or colour coding, lists, charts, mnemonics3. |

Clarifications:

1Well-structured problems (low fidelity) have only relevant information and are presented in such a way that the relevant information is properly labeled or easily identified.

2Ill-structured problems (high fidelity) have relevant and irrelevant information, unlabelled, and it is up to the student to determine the significance of the information and what to focus on.

Fidelity has to do with to what extent a problem or scenario has been simplified or structured for training purposes. Low fidelity to the “real world” involves simplifying and labelling significant information. High fidelity is to provide all the messy details that real-world problems have, without labelling or otherwise indicating the significance of, and including irrelevant information.

3Mnemonics involve word or letter and number combinations that are easy to remember that serve as a legend or “decoder ring” for the longer, more difficult item that requires memorization. For example:

- For the colours of the rainbow, the imaginary person Roy G Biv for Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet. Or, as my grade 11 FHS Physics teacher, Mr. Demerson used, VIBGOR the monster, which he would give with a roar and threatening gestures.

- Initialisms for the Great Lakes: HOMES: Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior.

- The phrase “Now I need a drink, alcoholic of course, after the heavy lectures involving quantum mechanics” to remember the first 15 digits of the mathematical constant pi: 3.14159265358979. The number of letters in each word correspond to the digit for that place in the sequence.

- Music: my STU French Immersion teacher had us sing the French irregular verbs to a Gregorian Chant in 1980, and I can sing/remember them to this day.

Teaching methods tips:

Within each class, also consider how to organize your material so that students can both learn and retain it. Some ideas to consider are:

- Find out what students already know, then add missing detail by using concrete examples (cases, scenarios, news items, things from the “real world”) and then move to the concept, model or theory.

- Start with a solution, conclusion, or model and work backwards to the question.

- For variety (and for the sake of students who think this way), give principles, concept, or theory and find/use examples from everyday life, the news, current events, social media, and student experience.

- Give students time to reflect, individually or through discussion, group work, and/or peer instruction on what and how they are learning.

- Build in practice time, with feedback, either in class or on assignments so that students learn to work with the concepts and can receive assistance with problem areas.

5. How students will demonstrate what they know and can do (assignments, tests, projects, etc.)

Your assessment methods should assess the outcomes or learning objectives (depending on the instruction organizational model you’re using) at the level indicated by the outcome. For example, if the learning outcome was at the application level, then the instructional activity would be at that level (or lead up to and end at that level—perhaps discussing material presented in class, then use peer instruction, then scenarios). The assessment, in turn, should also use scenarios, either as assignments or in tests or an exam.

6. How you can be sure that assessment activities measure what is important in the course

The principle here is that the assessment items are weighted to match the relative importance of the course topics and skills. For example, if 10 % of class time was spent on one specific outcome, then 10% of the assessment (e.g., 10 percent of the questions on the final exam) should be on that outcome, and as we saw in the previous section, assess at the highest learning level achieved.

References

Anderson, L.W., & Krathwohl (Eds.). (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

Blooms taxonomy for the Cognitive Domain.

Davis, B. G. (2009). Tools for Teaching. Jossey Bass, San Francisco.

Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Defining Intended Learning Outcomes

Sullivan, T. (n.d.) A Syllabus Course Production Checklist. University of Texas at Austin.

University of Waterloo Centre for Teaching Excellence teaching tips, Course Content Selection and Organization