Alternative systems

In the introduction to this module, we briefly described free market, planned, and mixed-market economies. It’s important to consider that there is no country following a purely free market or planned economy. Instead, countries use a mixed-market approach, falling along a spectrum from heavy government intervention and control to less intervention and control, depending on the politics of each individual country. Where a country falls on this spectrum can vary over time, especially as different political parties gain or lose power.

All of these economies share one key characteristic, however - they all use economic growth as a key measurement of how successful they are doing. Earlier in this module, we looked at different ways to consider economic growth. In this section, we’ll consider several economic systems that do not rely on the concept of economic growth.

Steady-state economies

A steady-state economy is exactly as it sounds. Rather than having an economy that grows, a steady-state economy stays steady over time, neither increasing or decreasing by significant amounts. In a steady-state economy, specific limits or targets are set on the amount of production and wealth created, and in most cases, on human population levels.

The concept of a steady-state economy is based on two key ideas. First, that the production of goods and wealth uses up natural resources and decreases the amount of energy, space, and resources for Earth’s ecological processes (on which all life on Earth depends, including humans). Second, that by keeping the economy in a steady-state, a balance can be reached between providing a good quality of life for humans while leaving enough for Earth’s natural systems, processes and biodiversity to be sustained.

The limits established in a steady-state economy are intended to allow for long-term sustainability, including promoting equity, reducing over-consumption, eliminating poverty and reducing environmental destruction. Criticisms of steady-state economics tend to focus on the idea that imposing limits is difficult to do, is a potential infringement of individual rights, and would weaken any individual countries that attempted to implement a steady-state economy compared to other countries continuing to follow a growth model.

There are no countries currently using a steady-state approach, however, Japan has been nearing a steady-state economy as its workforce ages and population growth has begun declining.

Sharing economies

The sharing economy is one that has been gaining popularity in Canada over the last several decades. It is spreading as ground-up initiatives, appearing in specific sectors and areas, such as ride-sharing, tool sharing, and so on. More traditional examples of the sharing economy are public libraries and community gardens.

Essentially, individuals share their access to a specific set of goods or services. This reduces the financial burden of purchasing or owning, decreases consumption, and supports cooperation and community-building.

Sharing economies have existed throughout human history, and while they can benefit from government support (as in the case of public libraries), they are fundamentally based on the choices and commitments of individuals. They can function within other types of economies.

Examples of sharing economies include:

- Tool libraries and makers spaces

- Co-operative communities or organizations

- Skill sharing or task exchanges

Many businesses, such as AirBnB, Vrbo, Uber, Udemy, TaskRabbit and more are based on at least some aspects of the sharing economy model.

Gift economies

In a gift economy, goods and services are freely given between those who have them to those who do not. Gift economies tend to value community connections and stability over personal or individual wealth or accumulation of material goods. Gift economies can either involve gifting without any expectation of return or with the implication that gift receivers will later gift back services, goods, political or social support, or will pass gifts on to others.

Like sharing economies, gift economies can also function within other types of economies. Many traditional Indigenous cultures followed a gift economy model, which ensured that resources were shared and growth of social status and connections within a community took the place of material wealth.

In the modern world, gift economies tend to appear as communities where certain types of goods or services are given freely without expectations of repayment or exchange. Examples can include online advice forums or communities (ex. Reddit), communities where items or services are offered for free to those who need them, freely shared art or information (ex. Wikipedia), and so on.

“The currency in a gift economy is relationship, which is expressed as gratitude, as interdependence and the ongoing cycles of reciprocity. A gift economy nurtures the community bonds that enhance mutual well-being; the economic unit is “we” rather than “I,” as all flourishing is mutual.” - Robin Wall Kimmerer

Focus on: Indigenous gift economies

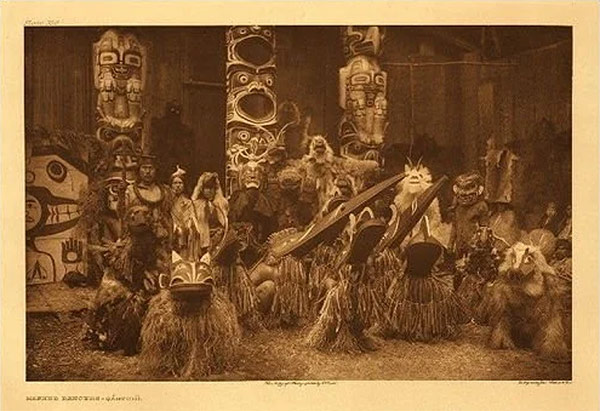

Gift economies are best known from Indigenous cultures such as the Kula exchange between villages in Papua New Guinea, the New Zealand Maori custom of koha, or the potlatches of various tribes from Canada’s west coast.

Image credit: New World Encyclopedia

A potlatch is a ceremonial gift-giving feast, generally occurring in celebration of an event, and intended to strengthen ties of community, reinforce hierarchies and social status or power and redistribute material wealth. Potlaches also provided an opportunity for leaders and communities to discuss and negotiate needs of their tribes and peoples, making them a form of government in addition to an economic system.

Potlatches were traditionally practiced by a variety of Indigenous groups living throughout the North American northwest until 1884, when the Canadian government outlawed them as part of the Indian Act. Some communities and individuals continued to practice potlatches or preserve cultural elements of them despite the ban, however, repercussions were often severe.

In 1951, the Canadian government repealed the law, and many peoples, such as the Haida of Haida Gwaii (located along the northern coast of British Columbia), have been attempting to reclaim their traditional practices and ceremonies, including the potlach.

Kwakwaka’wakw

The Kwakwaka’wakw are a people of the Pacific Northwest who have remained particularly dedicated to their heritage of the potlatch. In their tradition, a potlatch may be held for a variety of important family events and involved the host family giving away their possessions as gifts to be reciprocated by other participants at potlaches of their own. Potlaches could be used to honour friends and allies, or to humiliate enemies or rivals by giving them more than they could turn give themselves. Among the Kwakwaka’wakw, wealth was determined by how much a family could give away to others.

Several Kwakwaka-wakw chiefs have been instrumental in reviving the practice of potlatch within their communities. These include:

- Chief Mungo Martin, or Nakapenkim, who was awarded a medal by the Canadian Council for holding the first public potlatch after the government ban was lifted.

- Chief James Sewid, who was made an Officer of the Order of Canada in recognition for his many achievements

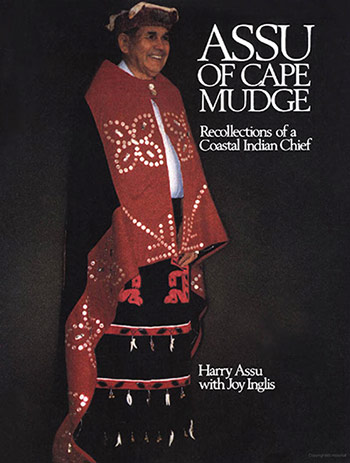

- Chief Harry Assu, whose family continues to be known for holding potlaches and author of the book Assu of Cape Mudge: Recollections of a Coastal Indian Chief

In addition to the efforts of individuals, the U’mista Cultural Society was founded in 1974 and serves the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples’ efforts to restore their cultural heritage and ensure it continues to survive into the future. Their permanent collection includes masks, regalia and other ceremonial objects that were seized and confiscated after an illegal potlatch in 1921.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.