Our history

The University of New Brunswick is situated on the traditional territory of the Wolastoqey people. The river that flows beside the university is Wolastoq (beautiful and bountiful river), along which live the Wolastoqiyik (Maliseets).

Wolastoq, renamed “St. John River” by early colonial authorities, was a vital part of life for the Wolastoqiyik, providing food and medicine and connecting the Wolastoqey villages alongside it. The land fed by the river was used for hunting, harvesting medicines and obtaining building materials. Daily life and culture were rich and varied. Ceremonies were performed, and knowledge was passed down through generations.

The University of New Brunswick is the first English-language university in Canada, but the first language spoken on this land is Wolastoqey latuwewakon. The first teachings on the land were the teachings of the Wolastoqiyik.

The Peace and Friendship Treaties of the 18th century allowed colonial settlers to establish settlements on Wolastoqey territory but, unlike many treaties across Canada, did not surrender any land. As part of the treaties, colonial settlers promised not to interfere with Wolastoqey fishing, hunting and traditional governing practices.

The idea for a university on this land was born as the American Revolutionary War drew to a close in the 1780s. Thousands of Loyalists gathered in New York City to await transportation to homes in other British colonies.

Among these Loyalists were Charles Inglis, a former interim President of King's College, New York (Columbia University); Benjamin Moore, later President of Columbia; and Jonathan Odell, minister, poet and pamphleteer. In the midst of war, privation and exile, they drew up a plan for the future education of their sons in their new home.

Recognizing that the new American nation would provide instruction only in revolutionary "Principles contrary to the British Constitution" and that the cost of an overseas education would be prohibitive, they urged the representatives of the British government to consider the "founding of a College... where Youth may receive a virtuous Education" in such things as "Religion, Literature, Loyalty, & good Morals..."

UNB began with a petition presented to Governor Thomas Carleton on Dec. 13, 1785. Headed by William Paine, the seven memorialists asked Carleton to grant a charter of incorporation for an "academy or school of liberal arts and sciences," which they maintained would result in many "public advantages and conveniences.”

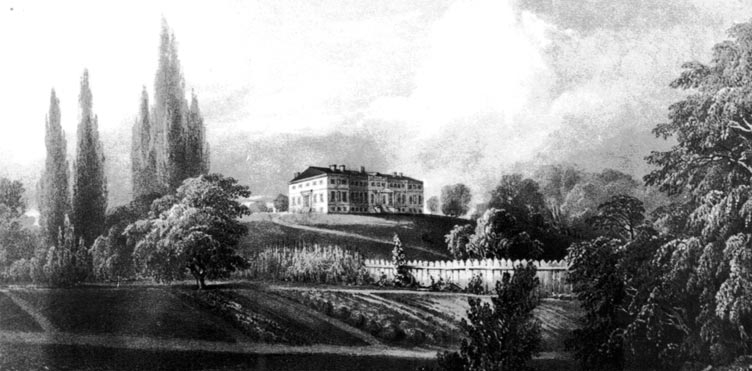

By 1829, the academy had become King's College and the building now known as Sir Howard Douglas Hall was officially opened.

King's College spent several tumultuous periods in conflict with members of the New Brunswick Legislature. Ostensibly, they were arguing over the issues of curriculum and religion, but the real issue was probably the cost of higher education.

Fortunately, King's did have its defenders, in particular, the elegant debater William Needham who, in the face of threats to burn down the college or to turn it into an agricultural school, made an impassioned speech that saved the institution from such ignominious fates. Through the efforts of Needham, Lieutenant Governor Sir Edmund Head and a few others, the Legislature was persuaded to reform rather than destroy the college.

On April 13, 1859, the act creating the secular, provincial University of New Brunswick was passed.

The post-First World War era brought the first great expansion of the physical facilities of the campus. In 1920, UNB consisted of Sir Howard Douglas Hall, the Science Building, the small Observatory, a small gymnasium and the Dominion Entomological Laboratory.

By 1931, Memorial Hall, a modern Library and the Forestry and Geology Building had been added.

The first university residence was a gift from Lord Beaverbrook who, growing up in New Brunswick as William Maxwell Aitken, studied law, and over the succeeding years developed an increasing interest in the welfare of the university.

Other buildings brought into being through his efforts and those of his family were:

- Lady Beaverbrook Gymnasium

- Aitken House

- Faculty of Law building

- Aitken Centre

In 1947, his Lordship became the University's Chancellor, to be succeeded by his son, Sir Max Aitken, in 1966 and in turn by Lady Violet Aitken, the wife of Sir Max, who served until 1993.

After the Second World War, returning veterans pushed registration to more than 770 in 1946, almost double the number enrolled in 1941. With this increased student population came a commensurate increase in faculty and course offerings, and a surge of building activity that transformed the campus.

The year 1964 brought three important developments: Teachers' College (the old Provincial Normal School) was relocated on the campus, to become incorporated into an enlarged Faculty of Education in 1973; St. Thomas University also relocated on campus, moving from Chatham and affiliating with UNB; and a second UNB campus was established in Saint John.

In 1981, the Mi’kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre opened its doors, providing academically rigorous programs enriched with First Nations content, perspectives and pedagogy.

UNB reached the end of its second century as a major provincial and national institution, offering a wide range of graduate and undergraduate programs in administration, arts, computer science, education, engineering, forestry, law, nursing, physical education and science. The university enters its third century proudly treasuring its past and eagerly driving the institution into the future.

Visitors

The middle years of the last century at UNB were marked by the Chancellorship and patronage of Lord Beaverbrook. Sometimes through his efforts, sometimes otherwise, we have had a number of important and distinguished persons visit the University.

- Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, July 12, 1967

- Princess Elizabeth, November 6, 1951

- Princess Margaret, August 7, 1958

- John Diefenbaker

- Robert Kennedy, October, 1967

- Senator John F. Kennedy was presented an honorary Doctor of Laws degree by UNB benefactor Lord Beaverbrook. On the same day in October 1957, the future U.S. president gave his now famous speech "Good Fences Make Good Neighbours" at the fall convocation.

- Linus Pauling, Nobel Laureate for Chemistry and Peace, October 1957

- Sir Robert Watson-Watt, inventor of radar, c. 1960

From the archives

Explore our 230 year history