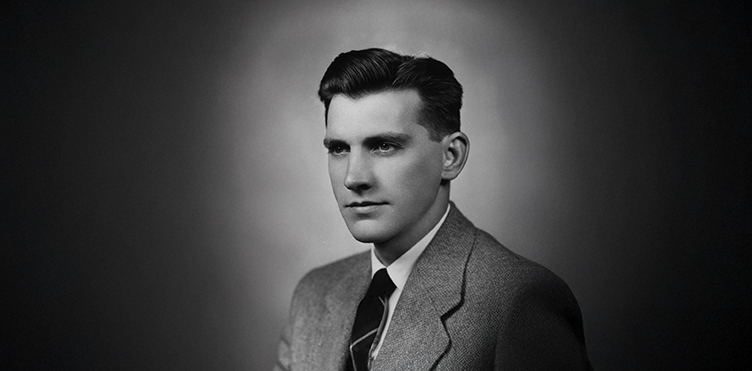

On June 12, 2025, the Honourable Gérard Vincent La Forest, C.C., K.C. (BCL’49), former Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, passed away peacefully at the age of 99, surrounded by his daughters in the comfort of his home.

Fondly remembered for his humble beginnings as “the boy from Grand Falls,” Justice La Forest was a towering figure in the UNB community, one of Canada’s most respected jurists, a brilliant legal scholar, and a devoted public servant.

In the days following his passing, tributes poured in from across the country. Among them, the Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin, P.C., C.C., former Chief Justice of Canada, who shared: “[Justice La Forest] possessed one of the finest legal minds I have ever encountered, shaped by a deep understanding of Canada’s dual legal traditions and marked by clear thinking, wisdom and creativity. He played a seminal role in shaping the jurisprudence that defined the new Charter era. La Forest was a great jurist and great human being. He may have left us, but he lives on the words of the judgments he authored and in the memories of those who knew him.”

Born on April 1, 1926, to parents J. Alfred La Forest and Philomène Lajoie, Justice La Forest was the youngest of their twelve children. He left home to pursue his undergraduate studies at St. Francis Xavier University, later earning his Bachelor of Common Law from UNB Law in 1949. That same year, he was called to the bar of New Brunswick. A man of quiet ambition and extraordinary intellect, he set off for Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar—only the third UNB Law grad ever to hold this distinction—earning a B.A. in Jurisprudence (1951) and subsequently an M.A. (1956). He later received an LL.M. (1965) and a J.S.D. (1966) from Yale University.

After a brief return to his hometown to practice law, Justice La Forest’s path led him to Ottawa in 1952, where he joined the federal Department of Justice. Three years later, he moved to Saint John to serve as legal advisor to K.C. Irving at Irving Oil. But it was the chance to explore the law at its deepest level—and to inspire the next generation of lawyers—that ultimately drew him to academia. In 1956, he joined the University of New Brunswick Faculty of Law as an Associate Professor, earning promotion to Professor in 1963. For more than a decade at UNB Law, he shaped the minds of hundreds of students through teaching, mentorship, and scholarship. In 1968, he moved west to become Dean of Law at the University of Alberta, a role he held until 1970.

In remembering the life and legacy of his former professor and colleague, Prof. (retired), Karl Dore (BCL’67) remarks: “‘Gladly wolde he lerne, and gladly teche.’ These famous words from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (1387) capture the essence of Gérard La Forest and his life's work in the academy, in government, and on the bench. I can personally attest to this, having had the great good fortune to be one of his many students. Gérard V. La Forest was a man for the ages.”

Justice La Forest returned to public service in 1970 as Assistant Deputy Attorney General of Canada, a post that placed him at the heart of a nation in transition. Over the next four years, he played a pivotal role in constitutional reform, helped establish the Canadian Human Rights Commission, and advanced negotiations on Indigenous land claims.

In 1974, he embraced a new challenge, joining the Law Reform Commission of Canada. Over the next five years, he was instrumental in shaping the federal government’s efforts to modernize family and criminal law. During this period, he also took a leave from the Commission to serve as Executive Vice-Chairman of the Canadian Bar Association Committee on the Constitution (1977–78).

He then moved back into academia, taking up the post of Professor of Law and Director of the Legislative Drafting Program at the University of Ottawa (1979–81). During this time, he also served as Chairman of the Special Enquiry into Kouchibouguac National Park (1980–81).

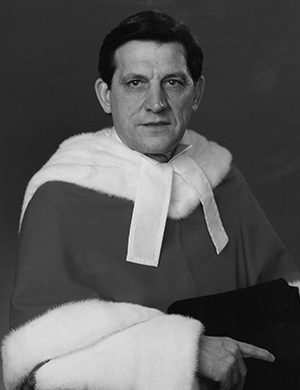

In 1981, Justice La Forest was appointed to the New Brunswick Court of Appeal, where he served with great distinction for four years.

“Justice Gérard V. La Forest’s contributions to Canadian law were both deep and enduring,” recounts the Honourable Marc Richard, Chief Justice of New Brunswick. “From his earliest days on the bench at the New Brunswick Court of Appeal, he brought to every decision a rare combination of intellectual rigour, clarity of thought, and practical wisdom. His judgments often illuminated complex legal principles in ways that were both precise and accessible, earning him the respect of jurists, practitioners, and scholars alike.”

On January 16, 1985, Justice La Forest reached the summit of the Canadian judiciary with his appointment to the Supreme Court of Canada, where he proudly served his country for 12 years until his retirement in 1997.

Justice La Forest was candid about the kind of judge he aspired to be. As Philip Girard observed in his article The ‘Atlantic Seat’ on the Supreme Court of Canada: An Endangered Species? (Osgoode Hall Law School of York University), La Forest outlined his judicial philosophy in a lecture delivered soon after his appointment to the Supreme Court. “I enjoy writing judgments, particularly where one can move the law forward for the better...[W]henever I come across a case where the law can be refashioned for the public good and private justice, I shall continue to do so—with relish!”

Justice La Forest was candid about the kind of judge he aspired to be. As Philip Girard observed in his article The ‘Atlantic Seat’ on the Supreme Court of Canada: An Endangered Species? (Osgoode Hall Law School of York University), La Forest outlined his judicial philosophy in a lecture delivered soon after his appointment to the Supreme Court. “I enjoy writing judgments, particularly where one can move the law forward for the better...[W]henever I come across a case where the law can be refashioned for the public good and private justice, I shall continue to do so—with relish!”

His obituary notes that “his jurisprudence was groundbreaking in many areas, including constitutional law, human rights, extradition, privacy, and public and private international law, and he was regularly cited throughout the common law world. One of his judgments is the only Canadian case included in a recent British text entitled Landmark Cases in Private International Law from 1750 to 2021.”

“Justice La Forest’s contributions to Canadian law were transformative,” says the Hon. Rosalie Silberman Abella, retired Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada. “He was on the Supreme Court at the beginning of the Charter, and he was an important brain on the team at that time. He made significant contributions in the area of equality with the Eldridge decision, which was pioneering—and, if I’m not mistaken, the first time the Court applied Andrews in a way that truly protected equality rights.”

Prof. Aloke Chatterjee shares Justice Abella’s praise of Eldridge. When Prof. Chatterjee first arrived at UNB Law, he had the good fortune to have an office next to Justice La Forest, who was then UNB Law’s Distinguished Legal Scholar in Residence.

“I was teaching Constitutional Law, and his landmark 1997 judgment in Eldridge v. British Columbia was on the syllabus. In Eldridge, a unanimous Supreme Court of Canada ruled that deaf patients had a right to sign-language interpretation when medically necessary. The judgment was, in many ways, ahead of its time and was a jurisprudential tour de force. It traversed the domains of Charter application, adverse effects discrimination, s.1 justification, and constitutional remedies. In a masterful judgment, Justice La Forest brought these various components of the Constitution into alignment in a manner that provided meaningful Charter justice to persons with disabilities. As a result, the judgment is a cornerstone of Disability Law in Canada. Justice La Forest’s judgment in Eldridge is my favorite case to teach, and I am glad I had the chance to tell him so when we were office neighbours.”

“I happen to really like his dissent in the PEI Reference,” shares Justice Abella. “I thought he was very perceptive and principled in his approach. He was brave and not afraid to either lead the way as part of a team or lead the way from the side as a dissenter. Where he was really luminous was in private law. He created the field of extradition, recognition of foreign judgments, and forum non conveniens, which are hugely important areas of law. We couldn’t get to where we are now without his footprints. He led the way.”

Stephen Penney, Professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Alberta, had the honour of clerking for Justice La Forest during the 1996–97 term. He was thrilled not only to clerk at the Supreme Court of Canada but also to work with a jurist he deeply admired. Though initially intimidated by Justice La Forest’s intellect, he quickly found him gracious, patient, and kind.

Reflecting on his clerkship, Prof. Penney pointed first to witnessing Justice La Forest’s work on the Provincial Court Judges Reference. “His impeccably reasoned, solitary dissenting opinion is a model of judicial humility and stands as an enduring rejoinder to the majority’s unbounded conception of the ‘unwritten’ Constitution.”

He also shared a more personal highlight: a lunch Justice La Forest and his wife Marie hosted at their Ottawa home. Prof. Penney recalls, “their affection for each other and devotion to their daughters was immediately apparent. Of all his remarkable accomplishments, this is undoubtedly the most important.”

Chancellor Wade MacLauchlan (LLB’81) remembers Justice La Forest as kind and supportive, especially during his time as Dean. As a young law professor at Dalhousie and director of the federal Common Law-Civil Law Exchange Program, MacLauchlan invited Justice La Forest to speak to students in 1987. After a lively exchange on comparative law and reform at the Supreme Court, the two spoke privately.

“While I was very much his junior, in both age and professional experience, he was open and reflective. We spoke about the well-known backlog—at the time—of Supreme Court cases awaiting decision. Justice La Forest observed that some members of the Court (unnamed) struggled to decide high-stakes matters. He said, ‘I don't have trouble with that. I enjoy making up my mind.’ Almost a decade later, as Justice La Forest neared the end of his 12.5 years on the Court and I had been dean at UNB, we knew each other quite a bit better. In a conversation about his leading opinions for the Court, he said, "I've had two big decisions redefining [a particular area of law]. I need one more to finish the job."

In 1999, Justice La Forest co-authored the Report of the Task Force on Aboriginal Issues with the Hon. Graydon Nicholas (LLB’71), C.M., O.N.B., LL.D. From May 1998 to March 1999, the two served as co-facilitators of the Task Force, holding more than 60 meetings across New Brunswick to foster dialogue and confront the systemic barriers facing Indigenous communities. They engaged widely—meeting with First Nations leaders, elders and youth, Aboriginal women, the Aboriginal People’s Council, the Union of New Brunswick Indians, the MAWIW Council, the Native Loggers Association, as well as representatives from the forest industry, environmental groups, professional organizations, and all levels of government. The Task Force also received numerous written submissions from Indigenous communities and other groups and individuals, ensuring a broad and inclusive record of voices.

“Gérard and I experienced mutual respect as we traveled tirelessly and listened to the voices of First Nation leaders. A significant moment was when a woman at Eel River Bar told us of a disabled child whose health needs required him to be airlifted to Halifax. Both the federal and provincial governments refused to help. Justice La Forest reminded the provincial government that such services were enjoyed by the military at CFB Gagetown, which was on federal property. The child was helped. It was an honour and privilege to get to know him and to work with him. Each time we saw one another, we would both smile and say, ‘We wrote a great Report.’ May you rest in peace my friend, and continue to look after your family from above as we celebrate your life here on Mother Earth.”

Following his retirement from the Supreme Court of Canada in 1997, Justice La Forest joined Stewart McKelvey as counsel and remained counsel for 22 years. Far from being simply retired, as counsel to Stewart McKelvey, he carried on his life-long work in the law by providing advice, opinions and counsel on numerous important national, international and constitutional issues to law firms, provincial and federal governments and agencies on diverse issues such as human rights, privacy, national and international taxation, language rights, the scope of federal and provincial powers, international and interprovincial boundary issues, including ocean boundaries, and Indigenous rights issues. His advice and counsel on international conflict of laws questions was sought by law firms across Canada and in the United States.

In remembering Justice La Forest’s enduring influence on both the profession and the people around him, Frederick McElman, CM, K.C. (LLB'78), Partner with Stewart McKelvey and long-time friend, reflects: “Beyond this continuing passion for and activity in the law, Justice La Forest also actively mentored younger (and some not so young) lawyers and students within the firm, generously providing his advice and counsel on the law, the history and meaning of law and the importance of the lawyer’s role in shaping the law. His interactions with younger lawyers were always thoughtful and practical, reflecting his previous role of university legal educator. Throughout his time with Stewart McKelvey, Justice La Forest always expressed interest in how lawyers could contribute to the development of the law through practice. Stewart McKelvey benefited greatly from Justice La Forest’s role as counsel for more than two decades, and the benefits of his contributions to the development of new lawyers at the firm will carry on for years. He will be greatly missed.”

Justice La Forest’s list of accomplishments and honours is as long as it is remarkable, reflecting a career that left an enduring influence on Canada’s legal landscape. His intellect and achievements have been recognized around the world.

He was named King's Counsel in New Brunswick in 1968. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, a Fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science, and he has been awarded honorary doctorates from eight universities, including the University of New Brunswick, where he received a Doctor of Civil Law (D.C.L.) in 1985.

“On the very special occasion of UNB's bicentennial in 1985, each Faculty was asked to choose one outstanding individual for an honorary degree,” recounted Prof. Dore “The Law Faculty's choice was The Honourable Gérard La Forest. In my citation for his degree, I said that Justice La Forest stands out as the most distinguished graduate in the entire history of our School. Justice La Forest was also the finest scholar in the history of our School.”

On October 8, 1992, to mark the 100th anniversary of the faculty, the UNB Law Library was officially renamed in honour of the Honourable Gérard V. La Forest—a space that has become a cornerstone of academic life for generations of students. His portrait keeps a watchful eye over the space, a quiet reminder of the dedication, intellect, and integrity that law demands.

On October 8, 1992, to mark the 100th anniversary of the faculty, the UNB Law Library was officially renamed in honour of the Honourable Gérard V. La Forest—a space that has become a cornerstone of academic life for generations of students. His portrait keeps a watchful eye over the space, a quiet reminder of the dedication, intellect, and integrity that law demands.

In 1998, after Justice La Forest’s retirement from the Supreme Court of Canada, UNB Law organized a symposium to celebrate his career and contributions. Judges, lawyers, and scholars gathered from across Canada and beyond, and the proceedings were later published as a book-length collection by the Supreme Court of Canada Historical Society (DeLloyd Guth, ed., 2000).

Chancellor MacLauchlan remembers the closing moments: “Gerry [as he was known by most of those present at the symposium] was the last to speak. He started out by responding to those who had spoken about his multifaceted career. He reminisced about a cartoon strip character from his youth called ‘Mr. Available,’ who was willing to take on all jobs. Justice La Forest joked that the title ‘Mr. Available’ might be used to describe his career.”

On November 16, 2000, he was invested as a Companion to the Order of Canada by Canada's 26th governor-general, Adrienne Clarkson. His citation reads: As Justice of the New Brunswick Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada, he brought keen analytical skills and a sense of compassion to legal decisions affecting the lives of millions. He is a constitutional expert and was an important member of the Law Reform Commission of Canada and, most recently, the Federal Task Force on Human Rights Legislation. His career, characterized by his great concern for the importance of privacy in modern society, has had an enduring influence on the institutions with which he has been associated.

In 2001, the Canadian Council on International Law (CCIL) acknowledged his deep contributions to the application of international law in Canada by awarding him the Read Medal, the CCIL’s highest distinction.

In March 2012, the La Forest Rare Books Reading Room was officially opened in the law library, ensuring the preservation of our historic legal collections for the benefit of future generations of law teachers, researchers, and scholars, as well as members of the Bar and the Judiciary.

To mark the occasion, UNB Law Professor David Bell (LLB’80) remarked, “[The La Forest Rare Books Reading Room] houses and displays print works and memorabilia from one of 20th-century Canada’s great judges and one of UNB’s most distinguished alumni. The Law Faculty is honoured to recognize in this way not only Mr. Justice La Forest’s career but especially all that he’s done, over many decades now, for UNB’s law program and our students.”

When he retired from the Supreme Court of Canada on 30 September 1997, Gérard and Marie, his cherished wife of 49 years, returned to their beloved New Brunswick. Shortly after their return, Marie fell ill, and Gérard devoted himself to caring for her at home until her passing in 2002.

Throughout his life, Justice La Forest never failed to acknowledge the profound influence of his family. At his Swearing-in at the Supreme Court of Canada on February 12, 1985, he spoke movingly about his wife, Marie, and the impact she had on his life:

“[T]he strongest influence in my life has been my wife, Marie. A product of a loving and accomplished family, the Warners, I found that happy combination of German with Scottish and Irish and a saving touch of French quite irresistible, and I still do. Her wisdom has avoided many mistakes, her strength and courage have helped us overcome many of the vicissitudes of life, and her ability (not yet, it must be said, wholly perfect) of overlooking my deficiencies have been a constant source of support. I owe her more than lies within the power of words to express. Her greatest gift to me has been our five daughters—Marie, Kathleen, Anne, Elizabeth, and Sarah. The presence of all of them here makes this happy moment complete. Three have done me the honour of following the path of law. Whether the others will follow remains to be seen. I wouldn’t want people to think that’s all we can do."

La Forest’s children grew up in a house where education, public service, and commitment to family were the central tenets that shaped the paths they would go on to follow.

Over the course of his extraordinary career, Gérard La Forest shaped the direction of Canadian law at every level. He will be remembered for his deep intellect, integrity, and unwavering commitment to justice, reflected in the hundreds of judgments, articles, and reports he authored. Through this body of work, he will continue to inspire generations of UNB Law students and scholars, as well as jurists the world over.

"Gérard La Forest was UNB Law's intellectual giant and the most influential jurist to graduate from our institution,” said Michael Marin, Dean of Law. “As we mourn his passing and extend our condolences to his family, we also reflect upon with great pride and admiration his contributions and ties to our Faculty."

The measure of La Forest’s influence and stature is perhaps best captured in the words of Justice Abella, who reflects: “He loved law. He loved—with humility—being able to contribute to the expansion of justice because he was a very fair and humane person, not just a jurist. You can’t have one without the other. And there was his friendship with Gordon Fairweather [a fellow 1949 grad], who was the same kind of statesman in the legal system—transcendently humane and courageous and committed to Canadian values. They had a partnership that was New Brunswick teaching Canada how it should think about justice. He loved his family. He was unabashedly devoted to his wife and children. Everybody knew they came first. His humanity was the core of who he was. He was the same in his judicial life and his personal life—a modest, kind, and compassionate scholar.”

Gérard La Forest’s legacy is written not only in the law but in the ideals he embodied and instilled in others. His memory will remain a source of inspiration for generations, carried forward by all who had the privilege to learn from him, work alongside him, or be guided by his example. We extend our deepest condolences to his family, friends, and all those whose lives he touched.